“Innovation in Education,” is an umbrella term that means different things to different researchers and educators. While there is no single definition, most can agree that it’s about enacting positive changes inside the classroom and the greater school community to better serve students.

Waldorf educators explored the questions around innovation at the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America 2019 Summer Conference — Responsible Innovation: A Collaborative Approach to Educational Freedom. Specifically, we looked to clarify ideals of innovating within and with respect for the core principles of Waldorf pedagogy.

Yet even with clear principles and missions, the guiding forces for how to accomplish innovation is much debated in all education systems and schools. Some see “education innovation” as a buzzword for ed tech. Others imagine it to be disruptive change from the top down to whip underperforming systems into getting better standardized test scores. Others still believe it must be teacher-driven change at the individual classroom level.

The whys are somewhat similar, the hows vary greatly, and the results? Everyone can agree that no matter the desired results, accomplishing them is complicated and often elusive.

The U.S. Department of Education Office of Innovation and Improvement is learning this first hand with their i3 grant program, which invests in innovative ideas put into practice in public schools nationwide. The Investing in Innovation Program (i3) has issued 172 Grants since 2010 and has spent $1.5 billion dollars.

Results have come in for the first 67 programs funded and, according to the Hechinger Report review, only 12 have had positive impact on student achievement. Many education researchers and experts, like Barbara Goodson at the education research firm Abt Associates Inc., are not surprised.

Goodson was hired to analyze the results of the i3 grant program, formally named the Investing in Innovation (i3) Fund, and she says, “It is really hard to change student achievement… learning is ultimately about changing human behavior and that is always difficult… so many other things — like nutrition, sleep, safety, and relationships at home — affect learning.”

She adds that the current measures of effectiveness, generally standardized test assessment, may be too broad to capture the benefits of many funded innovations.

This leads to a potentially more relevant question around innovation in education. Namely, how does an organization encourage, create, and measure what works in any given setting?

Lars Esdal, executive director of Education Evolving, a nonprofit organization working to improve public education, wrote about this topic at EdWeek in the article Four Dimensions of Innovation and The Strategy for Scaling it Up. He maintains that innovation cannot be a mandate. It must be a culture created within a school or school system. He believes we must “create opportunities and incentives for folks to design different and better learning experiences, but not require it.”

Once a culture is established that encourages change and new ideas, the system or framework for creating effective change is a well-researched topic. A foremost thought leader in the theory of systems change is Dr. C. Otto Scharmer, a Senior Lecturer at MIT and co-founder of the Presencing Institute. Scharmer has written a book examining the core principles and practices behind changing an organization.

Scharmer says the book, Theory U, works as “a framework and language that helps you locate yourself in the larger developmental framework of systems change. It’s a method that helps you move through phases. … to make visible the deeper structure that supports our best moments of leading and learning.”

In his interview in Leadership Change Magazine, Change on Many Levels, he speaks of the tenets and the actions behind inspiring change at an institutional level. He echoes Esdal’s belief that a culture must be open for change, but adds an additional layer of responsibility on individuals for openness — saying we must be willing to have “open hearts, open minds, and open wills.” Scharmer believes change is only possible if individuals are willing to “be authentic, reflective, and mindful.”

It is only then, according to Scharmer, that leaders are ready to take the actions needed which require they:

Stop and pay attention to what’s happening in the changing environment;

Let go of old methods and paradigms that no longer serve the cause or mission; and

Let new possibilities come from their higher or best selves.

But will all of these good intentions, processes, and ideas actually lead to innovation that works for students? As earlier efforts with i3 have indicated, there is either a failure in innovation itself large-scale or, more likely, a failure in the measurement of innovation.

Esdal squarely sets the blame on standardized tests. In his article, Life is Not a Standardized Test, he says, “We have fallen into the trap of valuing what we measure rather than measuring what we value.” He advocates instead for measuring what he calls, “collective outcomes” — critical thinking, analytical reasoning, problem-solving, and writing — to truly see the results of innovative initiatives.

Stanford Education professor and researcher, Linda Darling-Hammond, agrees. In her Edutopia article How Should We Measure Student Learning? 5 Keys to Comprehensive Assessment, she recommends establishing multiple sets of assessment alongside standardized testing. She encourages educators to develop clearly defined rubrics (or criteria) for assessing changes and development via student portfolios, presentations, and other special projects.

Innovation is geared toward improving important 21st Century skills like, she says, “recall, analysis, comparison, inference, and evaluation… and they are the kinds of skills that aren’t measured by our current high-stakes tests.”

The business world can lend credibility to expanding evaluations beyond hash marks and spreadsheets or scores and numbers.

Michael J. Mauboussin, Director of research at BlueMountain Capital Management and Professor at Columbia Business School in New York City, explores measuring success beyond statistics in his latest book The Success Equation. He delves into his core ideas in this Harvard Business Review article, True Measures of Success.

Mauboussin reminds us that what matters are measurements “that reliably reveal cause and effect.” Numbers are easy to measure, but are only a small part of a larger picture. Non-numerical measures, while more difficult to establish, are often more valuable. Mauboussin, in fact, has found that in the business world, those who can link up and measure non-numerical values and data have a better track record for improvement and innovation.

In the more practical and education-specific realm, Laura Thomas, Director of the Antioch University New England Center for School Renewal and Critical Skills Program, shares specifics on what these assessments can look like in her article 7 Smart, Fast Ways to Do Formative Assessment, also published by Eduptopia.

Thomas recommends simple tools for assessment delivered in a low-stakes environment to students such as student and teacher surveys, ungraded quizzes, in person interviews, and focused observation, to name just a few.

She says, “we can deploy [assessments] quickly, seamlessly, and in a low-stakes way—all while not creating an unmanageable workload… the point is to get a basic read on the progress of individuals, or the class as a whole.”

Regardless of the complexities of education innovation, the obligation to innovate is as essential as it is urgent. All educators must commit to seeking and embracing change. Together we can shift paradigms around the way things “have always been done” and make learning experiences relevant to our students, responsive to their unique identities, and tailored to their abilities.

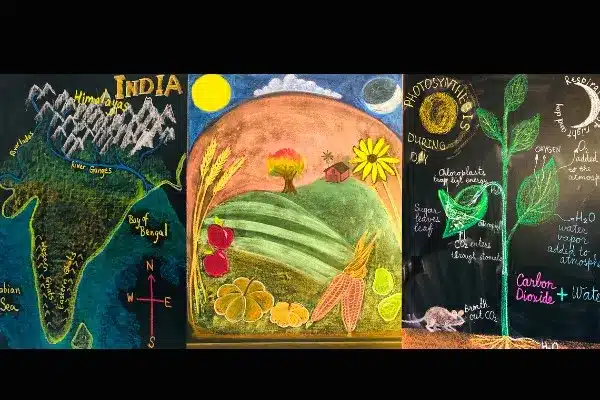

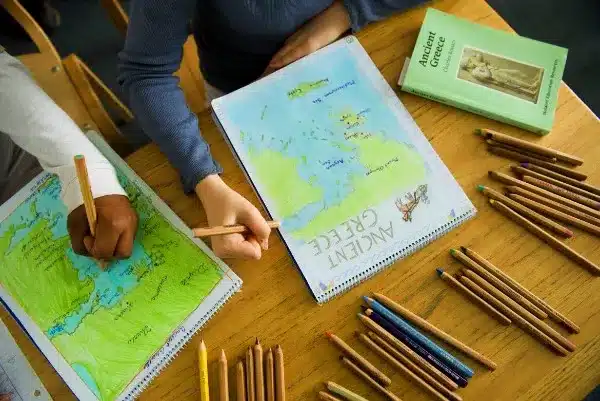

Photo Credit: Waldorf School of the Peninsula