We all want our children to be happy, and while this is traditionally thought of as an at-home concern, we send our kids to school hoping that they will have an emotionally enriching and balanced day.

Carol Gerber Allred, President/Founder of the Positive Action Program, geared toward fostering more positive classrooms, believes that families and students both expect and desire well-being at school, but unfortunately, testing culture has shifted the expectations of educators.

Here in her Educational Leadership article at The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development website, she says: “Unfortunately, the accountability requirements of No Child Left Behind have created a different definition of positive classrooms for many educators. For them, positive classrooms have come to mean places where students arrive at school ready to learn; work diligently to master academic standards (particularly math and reading); go home and accurately complete homework; and return to school the next day eager to learn more. Often, teachers are so focused on ensuring that students pass achievement tests that they have little or no time to address students’ social and emotional needs.”

Now educators and researchers alike are beginning to realize that overlooking well-being’s connection to learning is a mistake. Perhaps we all instinctively know that happy children will be more willing to learn and less distracted. Now science is backing up that intuition.

As researched and noted in this study by The German Department of Education, “Emotions are … closely related to cognitive, behavioral, motivational, and physiological processes, and therefore they are also important for learning and achievement.”

American researchers agree. In the report, Why All Children’s Dispositions Should Matter to Teachers, the authors cite the early childhood research of Tony Bertram and Chris Pascal, to “identify three core elements of effective learners: ‘dispositions to learn, social competence and self-concept, and social and emotional well-being.’

According to Bertram and Pascal only focusing on academic competency in students is “insufficient,” and they urge teachers to focus on “wider outcomes to sustain the development of young minds.”

Dr. Emma Seppala, Stanford researcher and author of The Happiness Track agrees, and discusses why well-being needs to be a priority in 21st century classrooms in this New York Times article, Letting Happiness Flourish in the Classroom.

She says, “Happy kids show up at school more able to learn because they tend to sleep better and may have healthier immune systems. Happy kids learn faster and think more creatively. Happy kids tend to be more resilient in the face of failures. Happy kids have stronger relationships and make new friends more easily.”

But how exactly do we define happiness or even “social and emotional well-being” in the classroom? Although there are various definitions for the term “well-being,” according to the oft-cited Evaluating and Promoting Positive School Attitude in Adolescents, social scientists define it as a “set of subjective feelings and attitudes toward school… Well-being in school consists of cognitive, emotional, and physical components, i.e., a learner’s thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations [at school.]”

And by this very specific definition of well-being, students who enjoy school while there have been shown to have better academic performance than their less joyful peers. As it turns out, there is a wellspring of studies about student well-being linked to better engagement and advanced academic performance.

Perhaps the most convincing research comes out of Harvard, in a recent study noting a correlation between a student’s level of self-reported happiness and GPA. Harvard Graduate School of Education lecturer, Christina Hinton, found that in elementary school through high school, student self-rated levels of happiness, defined by “students’ satisfaction with school culture and relationships with teachers and peers” positively correlates with motivation and academic achievement.

Co-founder of the NeuroLeadership Institute, Dr. David Rock, agrees that well being is a key part of achievement. In his research about the negative effect stress has on learning, he cites a growing body of research about positive emotions in relation to better learning.

He says, “People experiencing positive emotions perceive more options when trying to solve problems, solve more non-linear problems that require insight, [and they] collaborate better and generally perform better overall.”

So how do we make our classrooms more positive places that foster a sense of well-being?

According to Scott Hughes, Education PhD the simplest way to do this is to refocus: “It’s about kids before curriculum. . . . when we start placing other considerations ahead of children — curriculum assessments, accountability measures — some unhappy experiences started to emerge.”

Dr. Timothy Sharp agrees and, in his Education Review article, defines practical ways to refocus and foster well-being in class, such as:

- Develop a positive student/teacher relationship with each student.

- Engage students with relevant, interesting and compelling lessons.

- Help students identify their strengths. Specifically look for strengths in past experiences and discuss how to use them in future learning.

- Make students feel special while avoiding providing empty praise such as “you are so smart.”

- Cultivate hope and optimism by reminding the student of previous successes from hard work.

According to teacher and education leader, Elena Aguilar in her Edutopia article, Simple Ways to Cultivate Happiness in Schools, it really can be even simpler at its most basic level because children are made happy by simple things. She encourages teachers to help kids slow down, go outside, move in class, make music, and have quiet time.

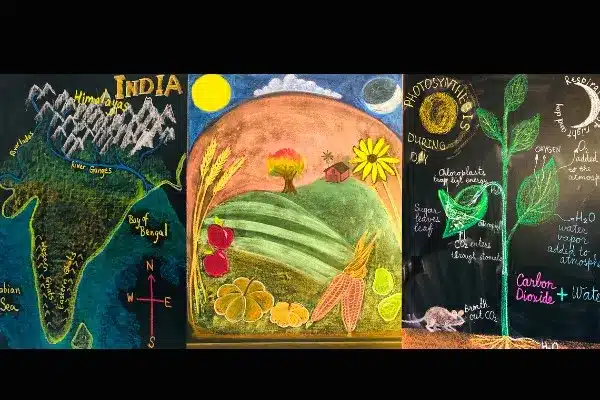

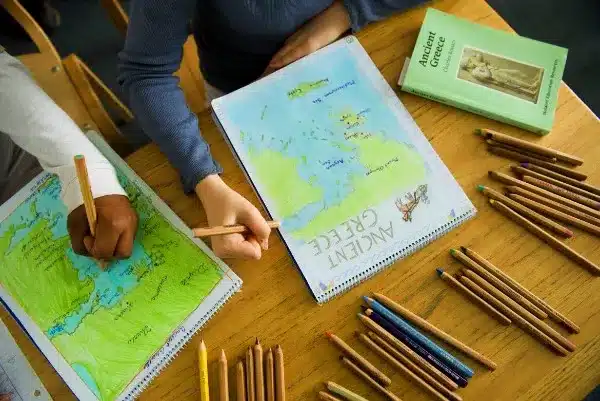

As Waldorf educators, we have known this for over a century. The key to promoting well-being, in addition to putting children’s needs before academic goals, is in teaching the right thing at the right time. And this, as Aguila wisely notes, often translates into letting our children just be children.

Photo credit: Detroit Waldorf School