“Divergent thinking” was a term coined by psychologist J.P. Guilford in 1967. Guilford was an early proponent of the idea that intelligence is not a unitary concept, as many after him, like Howard Gardner, would also propose.

Guilford was particularly interested in the fact that many creative people scored lower on standard IQ tests. He determined that this was due to their more lateral-type approach to the problems. They seemed to see more diverse possibilities as they engaged in problem solving.

IQ tests, as Guilford discovered, were based in measuring convergent thinking–a person’s ability to apply one set of rules to arrive at a single, correct solution. Divergent thinkers, on the other hand, can generate many varied solutions to one question.

Here in the 21st century, we are coming to understand and appreciate the role played by divergent thinkers. They are our inventors, innovators, entrepreneurs, and visionaries in all walks of industry, politics, and life. This appreciation for divergent thinking translates to a call for more respect of thought diversity in education. It is what leads experts like Ken Robinson to ask such rhetorical questions as, “Do schools kill creativity?”

It could be fairly said that many schools do not focus on creativity. And more fairly still, that schools focus primarily on convergent thinking. It only makes sense that convergent thinking skills are rewarded in a system that often encourages reiteration of correct answers given by teachers on tests, and rewards students for those exact, correct answers in grading.

While it may be tempting to see convergent thinking as negative, the call for educators should be about restoring more balance between the two types of thought. Good learners need to be well versed in both convergent and divergent thinking skills. Not only do students need both sets of skills for their schooling, but they need to realize that these ways of thinking are not mutually exclusive, and benefit studying and working in any field.

Take science for example. The deductive logic and reasoning that is the hallmark of the scientific method begins with convergent thinking. Once a hypothesis is stated, gathering facts and data, applying it to the question at hand, and deducing a logical answer are essential and essentially convergent-thought based. When the hypothesis is not proven, however, divergent thinking is best applied to the new problem at hand. Those too mired in convergent thought will sift, sort, and struggle through minutiae when faced with the larger questions: “Why did this fail?” and “What needs to change?”

This is why great theoretical scientists like Einstein are excellent divergent thinkers.

They engage in thought experiments, can imagine different scenarios and solutions, and are willing to apply wild theories and concepts that epitomize “out of the box” thinking.

So, how do we encourage this type of thinking in students when education is convergent-thinking-based by design?

Get Out of the Way…

Children are naturally divergent thinkers. This was the conclusion of a 2011 study, A riot of divergent thinking, published in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine: “A longitudinal study of kindergarten children measured 98% of them at genius level in divergent thinking. Five years later, when they were aged 8 to 10 years, those at genius level had dropped to 50%. After another five years, the number of divergent thinking geniuses had fallen further still.”

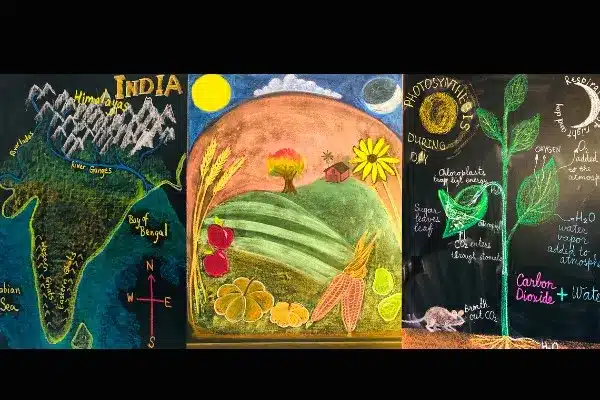

Data like this could lead to arguments that the best way to encourage divergent thinking is to simply get out of the way when it occurs naturally in the classroom. Especially in the younger grades. Let the children foster and use their imaginations, allow time for meandering lines of commentary and questions in study, engage their creativity through arts, and encourage the kind of wild brainstorming that naturally happens with younger students.

Defer Judgment…

In the younger grades and older ones too, deferring judgment would help students feel more comfortable engaging in their natural tendency for divergent thinking. This is not the same as eschewing logic in favor of silliness, but instead a holding off or delay of judging ideas. While opportunities for this may be limited in fourth grade math lessons, they would abound in fourth grade science or language arts classrooms.

When students are asked “why,” they should be given the time and space to answer from many different angles and should be encouraged to think in wild and creative ways. Topic changes could be seen as brainstorming and thus tolerated until the teacher feels the need to guide them back to the question at hand. Ideas can be used as springboards to combine and improve thinking by the class as a whole. If this is done while avoiding the judgment of ideas as either bad or good, then divergent thinking will happen.

Ask Unanswerable Questions…

In the real world, many questions are complex and do not have a single answer. Why then do educators often only ask the questions that have one answer? The premise of it is simple: pose real life, complex problems to students and help them learn to use both divergent and convergent thinking to progress towards different probable solutions.

Students will not only learn divergent thinking in these scenarios, but older students can be guided to consider relevant issues to their lives and society as a whole by addressing questions like: “How could we feed the world without industrial farming and genetically modified plants?”

Turn Q&A to A&Q…

Otherwise known as Socratic Inquiry, this approach to learning presents an answer and then asks the questions–how, why, what? This type of inquiry immediately calls for divergent thinking in students as it taps into natural curiosity to draw out ideas.

As an example in the classroom, students attempt to lift a desk. Then they lift it with a single rope and pulley. Then they add additional pulleys. What do the students notice as they move through this process? What is happening? Why? And so forth.

Normalize Failure…

Creating a space in the classroom for failure, and helping students embrace it, is a key step in learning as it takes the shame out of taking risks. Divergent thinking is, at its core, a willingness to step away from the “right” answer to consider other possibilities. Students who are ashamed or afraid to fail will resist anything beyond convergent thought. They will be obsessed with doing it right and getting it right and will believe that “right” is one thing. By normalizing failure, teachers can encourage students to approach problem solving in nonlinear, divergent ways.

If we can balance education’s approach between convergent and divergent thinking and help students learn to master, or at least appreciate, both of these approaches to thought, it will help them live in a world of expanded possibility. Then, ultimately and ideally, these students can take their expanded minds, theories, and problem-solving prowess out into the 21st century to make our world a better place.

Photo credit: Waldorf School of Baltimore